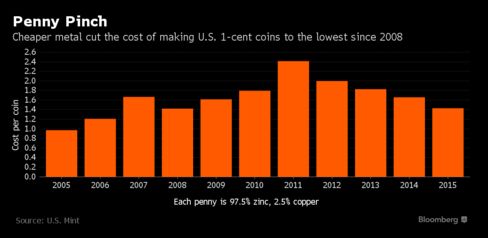

Sarhan in Bloomberg: Penny Cheapest in 7 Years as Zinc Rout Benefiting U.S. Taxpayers

- Mint spent 1.43 cents to make each coin last year, down 14%

- The last time a penny cost 1 cent to make was 11 years ago

While the billions of new U.S. pennies put into circulation every year still cost more to make than they are worth, the government is catching a break from the collapse in metals prices. Each one-cent coin — made almost entirely of zinc — cost 1.43 cent to produce last year, down 14 percent from a year earlier and the lowest since 2008, according to data from the U.S. Mint. As recently as 2011, the price tag was 2.41 cents. Since then, zinc prices fell 34 percent from a peak as demand slowed in China, the world’s biggest buyer.

The last time a penny cost what it was worth was in 2005. While the Mint doesn’t foresee breaking even on the coin, cheaper metal last year helped to boost output 16 percent to 9.155 billion pennies. For taxpayers, that meant the U.S. made 1.235 billion more pennies for about $555,000 less than it spent a year earlier. Made almost entirely of copper until 1982, the coin is now 97.5 percent zinc, a metal used mostly to help prevent rust and found in all sorts of products, from electronics to paint to sunscreen.

“If you look at zinc, specifically with respect to the penny, it’s very clear that you’re in a bear market, continuing to hit new lows,” said Adam Sarhan, the chief executive officer of Sarhan Capital in Bay Hill, Florida. “Demand is waning across the globe, and until we see a bullish catalyst, the path of least resistance is remaining lower for the foreseeable future.”

That would be good news for coin makers, including the U.S. Mint, which used about 25,358 metric tons of zinc to make pennies last year. On Jan. 12, zinc tumbled to a six-year low of $1,444.50 a ton on the London Metal Exchange, after a 26 percent plunge in 2015 that was the biggest annual decline in seven years. Prices had recovered to $1,725 on Thursday.

Penny Blanks

Low zinc costs may not last. Global demand outpaced production by 50,000 tons in 2015, and the market will see a deficit this year of about 53,000 tons, forcing manufacturers to draw down inventories, according to analysts at RBC Capital Markets. The bank forecasts a “modest” rebound in demand this year and next, after a slowdown in 2015. Zinc will average about $1,984 this year, the RBC estimates.

High costs have helped fuel a long-running debate about whether the U.S. should abandon the penny. Zinc reached a record $4,580 a ton in 2006, and even though prices have dropped, the average since then is more than $2,100. The Mint has been losing money on each new coin for a decade. President Barack Obama added to the pressure in 2013, when he said the penny was a “good metaphor” for some larger problems of government.

Americans for Common Cents, an organization whose primary sponsors include Jarden Zinc Products, argue that the penny still has benefits. Without a one-cent coin, product prices would be rounded up to the nearest nickel, which might hurt working families, said Mark Weller, the group’s executive director.

Cash Registers

Opponents first raised the prospect of abandoning the coin in 1990 — well before the Mint started producing the penny at a loss. At the time, a lobbying group that included the copper industry was fighting to replace the paper dollar with the dollar coin, but the proposal wasn’t catching on. Group members speculated the problem might be that there wasn’t enough room in cash registers, so they proposed abandoning the penny to free up space, Weller said.

“There’s always going to be a need for cash and for coin, and the Federal Reserve’s surveys tell us that there’s over 10 million Americans who are unbanked or underbanked,” Weller said. “Not only will you have an overall rounding tax on the economy if you didn’t have the penny around, but you would have a disproportionate impact on those that could least afford it.”

Under terms of a long-term contract, Jarden Zinc Products in Greeneville, Tennessee, supplies penny blanks that the Mint stamps with the images of President Abraham Lincoln on one side and a union shield on the other. The cost of the blanks is based on a fixed fabrication charge and the previous month’s average spot price for zinc traded on the LME and copper on the Comex in New York, Michael White, a U.S. Mint spokesman, said in an e-mail. The Mint doesn’t provide information on its fixed fabrication charge.

“We are happy any time we can take advantage of the market for the benefit of the American taxpayer,” White said.

LINK: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-03/losing-on-every-new-u-s-penny-got-less-painful-as-zinc-plunged